The gleaming promise of autonomous vehicles has long been accompanied by an uncomfortable question: who bears responsibility when these machines kill? As self-driving cars transition from science fiction to public roads, a troubling legal vacuum has emerged around accountability for fatal accidents involving artificial intelligence systems. This gray area leaves victims' families in limbo while manufacturers, regulators, and legislators scramble to define new frameworks for the age of machine decision-making.

Recent high-profile crashes have exposed the inadequacy of existing liability laws. When a pedestrian was struck and killed by an autonomous test vehicle in Arizona, the ensuing legal battle revealed startling gaps in traditional negligence doctrines. The company argued its AI behaved as programmed, while prosecutors struggled to apply human driver standards to algorithmic judgment calls made in milliseconds. Courts find themselves interpreting traffic laws written decades before anyone conceived of vehicles without steering wheels.

The heart of the problem lies in translating analog-era legal concepts to digital decision-makers. Traditional tort law distinguishes between manufacturer defects (strict liability) and operator error (negligence). But when a machine learning system evolves beyond its original programming through neural networks, these categories blur uncomfortably. A vehicle's "choice" to swerve into one obstacle rather than another may reflect training data biases rather than coding flaws—raising philosophical questions about whether AI can truly "decide" in the legal sense.

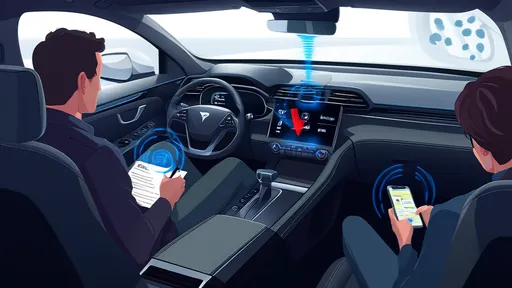

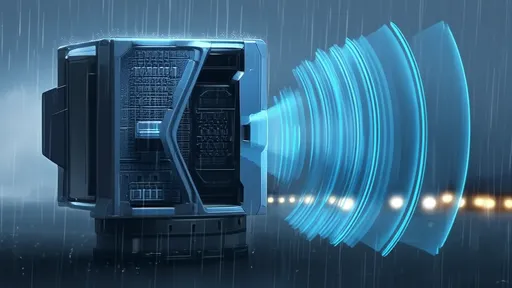

Insurance models compound the confusion. Current auto insurance frameworks assume human risk factors like age, sobriety, and attentiveness. Autonomous systems render these metrics meaningless, forcing insurers to calculate premiums based on software version numbers and sensor reliability statistics. Some providers have begun offering "algorithmic liability" policies, but these remain untested in widespread litigation.

Manufacturers walk a tightrope between innovation and accountability. Internal documents from several automakers reveal intense debates about how much control to retain over self-driving systems. Fully autonomous vehicles promise greater safety by eliminating human error, but also assume catastrophic failure responsibility. This has led some companies to deliberately limit their vehicles' operational domains—a strategy that may reduce legal exposure but frustrates regulators pushing for broader adoption.

The regulatory landscape resembles a patchwork quilt. Some jurisdictions treat the AI system as the driver, others designate the human occupant (if present) as ultimately responsible, while a few have created entirely new categories of "vehicle operators" that could be corporate entities. This inconsistency creates headaches for manufacturers developing vehicles for national markets and raises troubling questions about forum shopping in wrongful death cases.

Consumer protection laws offer little solace. Traditional product liability requires proving a specific defect, but neural networks' decision-making processes often resemble black boxes—even to their creators. Several courts have already ruled that plaintiffs cannot compel disclosure of proprietary algorithms, leaving families of victims unable to demonstrate how or why fatal decisions occurred. This evidentiary hurdle may require entirely new standards for transparency in machine learning systems.

International approaches highlight the depth of the dilemma. The European Union favors strict manufacturer liability but struggles to define what constitutes "reasonable" AI behavior. China has implemented real-time data monitoring requirements, creating records of system states before crashes—a solution that raises privacy concerns. Meanwhile, some U.S. states have essentially granted immunity to autonomous vehicle developers as part of economic development incentives, setting up potential conflicts between state and federal courts.

Legal scholars propose radical solutions ranging from treating AI systems as legal persons (complete with "driver's licenses" that can be revoked) to creating no-fault compensation funds similar to vaccine injury programs. The most pragmatic suggestions involve adaptive regulations that evolve alongside the technology, but such frameworks require legislative agility rarely seen in government bodies.

The human cost of this uncertainty becomes apparent in courtroom testimony. One grieving spouse described the surreal experience of deposing engineers about "what the car was thinking" during the milliseconds before impact. Another family's attorney recounted the challenge of arguing against a defendant that wasn't a person but couldn't be examined like typical machinery either. These emotional narratives underscore how existing legal structures fail to address the unique trauma of deaths mediated by artificial intelligence.

As the technology advances faster than the law can adapt, a troubling precedent emerges: the richer and more technologically sophisticated the defendant, the harder it becomes for victims to obtain justice. This imbalance threatens to erode public trust in autonomous vehicles precisely when their safety benefits—reduced drunk driving, fewer traffic fatalities overall—could save thousands of lives annually. The legal vacuum surrounding autonomous vehicle fatalities represents more than a technical loophole; it's a fundamental challenge to how societies allocate responsibility in an increasingly automated world.

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025

By /Jun 14, 2025