In a groundbreaking initiative that could reshape the future of tropical agriculture, scientists have begun field trials of genetically edited cacao trees designed to resist devastating viral infections. The experiments, conducted deep within the biodiverse rainforests of South America, represent a daring fusion of cutting-edge biotechnology and ecological conservation.

Theobroma cacao, the chocolate tree, faces existential threats from swelling virus epidemics that have already wiped out up to 30% of crops in major producing regions. Traditional breeding methods proved too slow to outpace rapidly evolving pathogens, prompting researchers to turn to precise gene-editing tools. "We're not introducing foreign DNA," emphasized Dr. Elena Vargas, lead researcher at the International Cacao Institute. "We're making surgical adjustments to the plant's own genetic code to enhance its natural defense mechanisms."

What makes these trials particularly remarkable is their location within intact rainforest ecosystems rather than controlled agricultural stations. Researchers deliberately chose sites where edited saplings grow alongside their wild counterparts and diverse flora. This unconventional approach allows scientists to study how the modified trees interact with complex ecosystems while monitoring viral resistance under natural conditions.

Early observations have revealed unexpected ecological benefits. The edited varieties appear to maintain all the chemical signals crucial for pollinator attraction while demonstrating remarkable resilience against cacao swollen shoot virus (CSSV) and other pathogens. Birds and insects continue visiting the trees at rates indistinguishable from unmodified specimens, easing initial concerns about potential ecological disruptions.

However, the project hasn't been without controversy. Some indigenous groups have expressed reservations about introducing biotech organisms into ancestral forests, despite detailed consultation processes. "The trees remember," remarked Tukumã Pataxó, a leader from the nearby Pataxó community. "We want guarantees that these changes won't make the forest forget how to be a forest." Scientists have established continuous monitoring systems to address such concerns, tracking everything from soil microbiota to canopy interactions.

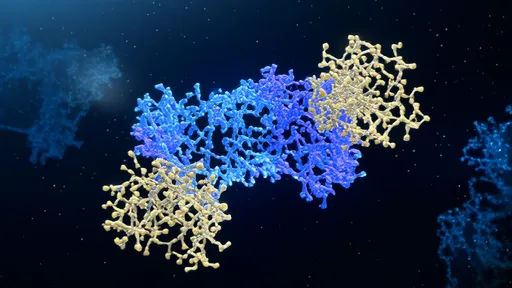

From a technical perspective, the editing focused on enhancing the plant's RNA interference pathways - a natural antiviral defense system present in most organisms. By making specific tweaks to proteins involved in this process, researchers created trees that can recognize and dismantle viral genetic material more efficiently. The modifications target highly conserved viral components, making it difficult for pathogens to evolve resistance through mutation.

As climate change alters disease patterns across the tropics, such innovations may become increasingly vital for protecting both agricultural livelihoods and forest ecosystems. The cacao trees serve as a test case for broader applications - researchers speculate similar approaches could protect coffee, bananas, and other culturally and economically significant crops vulnerable to viral epidemics.

The trials coincide with growing recognition of cacao agroforestry's potential as a conservation tool. Well-managed cacao plantations can preserve biodiversity while providing sustainable income for forest communities. Virus-resistant varieties could make such systems more viable by reducing the need for pesticides and preventing the agricultural expansion that often follows crop failures.

Data from the first eighteen months appear promising, with edited saplings showing infection rates 80% lower than control groups while maintaining normal growth patterns. Researchers caution that several more years of observation are needed to assess long-term impacts. The team has committed to publishing full environmental risk assessments regardless of outcomes, setting a new transparency standard for such projects.

This experiment represents a delicate balancing act between human ingenuity and ecological humility. As Dr. Vargas noted during a recent site visit, "We're not trying to conquer nature with these tools. We're trying to give vulnerable species a fighting chance in an increasingly unstable world." The rustling leaves of the experimental grove, alive with insects and birds, suggest that for now at least, the forest continues remembering how to be a forest.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025