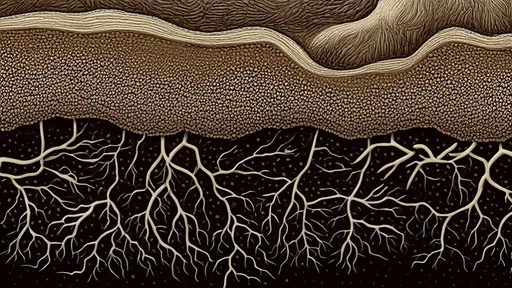

The dense, tangled roots of mangrove forests have long fascinated scientists with their extraordinary ability to thrive in saline environments. Recent breakthroughs in genetic research have uncovered a potential game-changer: the horizontal transfer of salt-tolerant genes between mangrove species. This discovery not only rewrites our understanding of mangrove adaptation but opens startling possibilities for agricultural innovation in an era of rising sea levels and soil salinity.

Deep within the brackish waters where freshwater meets the ocean, mangroves engage in a silent genetic barter system. Researchers at the Coastal Genomics Institute have identified mobile genetic elements carrying salt-resistant traits migrating between unrelated mangrove species through microbial intermediaries. This natural gene-sharing network functions like an underground information highway, allowing coastal plants to rapidly acquire survival advantages without waiting for generational evolution.

The mechanism appears to involve specialized bacteria that incorporate mangrove DNA fragments and transfer them to neighboring plants. Dr. Elena Voznesenskaya, lead author of the Nature Wetlands Ecology study, describes this as "a form of interspecies mentoring where experienced mangroves tutor their neighbors through genetic material." Her team documented cases where Rhizophora mangle trees transmitted ion-transport genes to adjacent Avicennia germinans specimens across taxonomic boundaries.

Field experiments in Florida's Ten Thousand Islands demonstrated the practical implications. When researchers introduced salt-stressed Laguncularia racemosa saplings to mature Conocarpus erectus populations, the young trees developed salt-excreting leaf glands within eighteen months - a trait absent in their genetic lineage but common in their mentors. Genomic sequencing revealed clusters of foreign DNA near root development loci, suggesting targeted incorporation of beneficial traits.

Agricultural scientists are racing to harness this phenomenon. The International Rice Research Institute has initiated trials inserting mangrove-derived salt tolerance genes into staple crops using the observed natural transfer mechanisms rather than artificial genetic engineering. Early results show promise, with test plots of modified rice surviving irrigation water containing 12% seawater concentration - previously considered impossible for conventional varieties.

Environmentalists caution that human intervention in this delicate genetic exchange requires careful oversight. "We're dealing with an ancient, self-regulating system," warns marine biologist Rajiv Singh. "While the applications could help combat food insecurity in coastal regions, we must avoid disrupting mangrove ecosystems that already protect shorelines and sequester carbon at unparalleled rates."

The discovery also reshapes fundamental botanical paradigms. Traditional models of vertical gene inheritance appear insufficient to explain mangrove resilience. Dr. Voznesenskaya's team has proposed a new framework they term "ecological genomics," where a plant's genetic identity becomes fluid, continuously shaped by its biological neighborhood as much as by its ancestry.

As climate change accelerates land salinization, understanding these natural genetic transfer systems grows increasingly urgent. The mangrove's secret genetic commerce offers both hope and caution - demonstrating nature's sophisticated adaptation mechanisms while reminding us how much remains to be learned about life's interconnectedness. Research continues across seventeen mangrove habitats worldwide, mapping this hidden web of genetic cooperation that may hold keys to sustaining life on our changing planet.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025