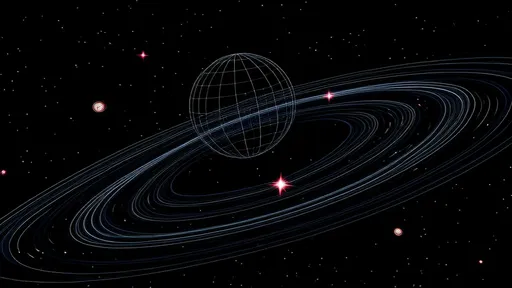

For decades, astronomers have grappled with a fundamental question: How fast is the universe expanding? The answer, encapsulated in the Hubble constant (H0), has remained frustratingly elusive, with conflicting measurements from different methods creating what scientists call the "Hubble tension." Now, a groundbreaking approach using gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime caused by cataclysmic cosmic events—is emerging as a promising new tool to resolve this mystery.

The Hubble Tension: A Cosmic Conundrum

The Hubble constant represents the rate at which the universe is expanding, a cornerstone of modern cosmology. Yet, two primary measurement techniques—observations of nearby celestial objects (like Cepheid variables and supernovae) and analysis of the cosmic microwave background (CMB)—yield inconsistent values. The former suggests a faster expansion rate, while the latter points to a slower one. This discrepancy, spanning nearly 10%, has persisted despite increasingly precise measurements, hinting at potential gaps in our understanding of physics.

Enter gravitational waves, the cosmic messengers first detected in 2015 by LIGO. These waves, generated by collisions of neutron stars or black holes, carry unique information about their origins. When paired with electromagnetic observations (like light from a neutron star merger), they offer a novel "standard siren" method—akin to a cosmic yardstick—to measure distances independently of traditional techniques.

Gravitational Waves as Standard Sirens

The term "standard siren" is a nod to "standard candles," like supernovae, whose known brightness helps gauge cosmic distances. Gravitational waves, however, provide a direct measure of distance without relying on the cosmic distance ladder’s rungs. By analyzing the waveform of a merging neutron star binary, scientists can infer the system’s distance from Earth. Combined with the redshift of the accompanying light (which reveals how much the universe has stretched since the event), this yields a fresh estimate of H0.

The 2017 detection of GW170817—a neutron star merger accompanied by a gamma-ray burst and optical afterglow—marked a watershed moment. Initial calculations from this event suggested an expansion rate straddling the existing divide, though with large uncertainties. Future observations, especially with next-generation detectors like the Einstein Telescope or LISA, promise to sharpen these measurements dramatically.

Why This Matters: Beyond the Hubble Constant

Resolving the Hubble tension isn’t just about nailing down a number. It could unveil new physics—perhaps undiscovered particles, exotic dark energy behavior, or modifications to Einstein’s gravity. Gravitational waves, unaffected by the dust and gas that obscure light-based observations, provide a pristine channel to test these possibilities. Moreover, as the sample of standard sirens grows, astronomers will map the universe’s expansion in three dimensions, probing whether H0 varies across space or time.

Challenges remain. Neutron star mergers are rare, and current detectors can only "hear" them within a limited cosmic volume. Upgrades to LIGO and Virgo, alongside new observatories, will expand this reach. Meanwhile, theorists are refining models to extract maximal information from each event, including those involving black holes, which lack electromagnetic counterparts but are far more abundant.

The Road Ahead: A New Era of Cosmic Audition

As gravitational-wave astronomy matures, it’s poised to revolutionize our cosmic ledger. Within a decade, a catalog of standard sirens may finally reconcile the Hubble tension or, more excitingly, cement the need for physics beyond the Standard Model. Either outcome would reshape cosmology. For now, each chirp from a distant collision brings us closer to decoding the universe’s expansion—one ripple at a time.

In the words of one researcher, "Gravitational waves aren’t just another tool; they’re a whole new sense. We’re not just seeing the cosmos anymore. We’re listening to it." And what it’s telling us could rewrite the textbooks.

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025

By /Aug 14, 2025